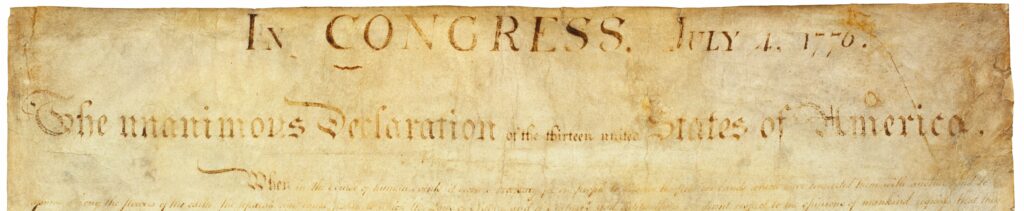

The U.S. Declaration of Independence stands as a physical document written for an express purpose at a point in time. It also represents a cornerstone of evolving enlightenment. What meaning does the physical artifact itself provide?

The year is 2072.

The written word is everywhere, and AI authors most of it. Human authorship is not unknown, but it is an art now, not a skill. A writer is like the artisan, who works with woods and metals, who designs careful works of craft for audiences desiring “soul” in contrast against the cheaper, more practical assembly-line alternative. The the art of writing, word by word, is likewise delegated now to the craft of the written word. In this way it is nearly a reflection of the past into the future — only a relative handful of “writers” now ply their trade in any meaningful way.

An apprenticing writer endures years studying form, prose, diction, details of grammar, symbolism, synechdoche, and structure to gain the skill of creating deep, meaningful, multi-layered forms of the written word. The master craftsman has elevating writing to something sublime. In fact this has always been an element of writing, but for so long, the duty of storytelling, in plainer form and for the simpler but worthy cause of entertainment, fell also to the writer. Now, such a task concerns the human author no longer….

Outside of the writer’s sphere of art, the written word remains as common as it is prosaic. The power of computational technologies — initially called “AI” and now so ubiquitous that no term is needed to identify it — has made generating written works as simple as running the dishwasher, and much more pleasant. You’d like to read a new fantasy novel this weekend? Generated in an instant, in your preferred style. Fan-fiction about your favorite cinematic universe? Whole tomes delivered in moments; enjoy your endless personalized content.

None of this output is high culture, none of it is deeply mature writing, but all of it is uniquely catered to the desires of the reader, all of it is of reasonable quality, and all of it can be built in such a brief span of time as to render a lack of personalized writing unthinkable. And the copyright laws came right along when stakeholders realized how much money was to be made in rolling with the punches…a nominal fee on every use of the word “Marvel” adds up fast when thousands of fans push the buttons for new comics every week.

So the writing continues, and the reading, too, which picked up noticeably as a predictable result of catering to every little whim (with some ongoing efforts to rein in the worst of the taboo found at the odd edges of literature). The concept of a “book” feels outdated to many readers; the desiring consumer simply expects some new piece of content, usually filled with the characters and themes they already like, and built to a form they enjoy — comic, short story, dialogue, interactive form, or the old standby, the novel.

Video, too, remains as big as ever, but readership has grown to nearly match the volume being generated. And why not? You can have your phone read you a new story about your favorite topic, written organically in your personal idiom without you having to explain, striking all your most enjoyed notes (including debauchery) and kept coming at the cadence you want — this is more alluring than any light novel written by human hand ever could have been.

* * *

That fragment is one possibility. Speculative, but realistic. Probable, even. And maybe the grounds for a fun story I wish I had time to write (hey, maybe with AI…)

Let’s pivot: That thought experiment was book as art; what about book as repository of information?

1. Virtual* content is ephemeral. This content is impermanent without our constant efforts to maintain it. Physical media expires, too, on a different scale — sometimes vastly different: A book from hundreds of years ago. A cuneiform tablet that has lasted three thousand five hundred years. Painted diagrams on a rock wall dating to the mesolithic. All readable, interpretable, comprehensible (usually).

In some cases the creator took effort to store it; sometimes not even this intervention was available or necessary. Virtual content, even if it would last this long (as perhaps on a tape in a vault) would present a challenge to decipher in a different world. We could imagine that the future world of a thousand or ten thousand or a hundred thousand years from now is sufficiently complex that even without knowledge of the paradigms and protocols we use to encode and write a digital medium, it could still be reverse engineered. We perform similar tasks already. But this requirement overlays a new challenge on the already difficult challenge of data preservation. Can we expect such a high standard for the capacities of future researchers and historians?

2. Virtual content is mutable. What it was, it may not always be. Like memory, with every access comes the possibility for edit and degraded quality on rewrite. Backups and distribution of content provide a fascinating fail-safe. It seems no matter how often content is deleted or removed, banned or outlawed, it finds its way back — for better or for worse. What that content represents, at the point of consumption, can only be stated by the viewer, at the time, with that particular copy.

Here is a video I am watching. Did you watch the same video? Was it edited since then? Is it the same version? We create mechanisms to audit or verify: blockchain, checksums, integrity checks; does it help? All we can say even with these is that such and such a piece of content is “verified”; but I may have a different, newer, or older, or better, or more interesting version of that content and which one is the “real” one when everyone across the world has seen mine?

3. Physical content is non-negotiable. That is, not negotiable in its form. Further content may alter, amend, revoke, or deem the content incorrect or meaningless — the content itself remains, and remains interpretable by all who view it if they have the necessary knowledge. Marginalia only add to the content. Later works don’t change the original substance. Strike words out of the text itself and they can still be read. Only true destruction ruins it and even this has been overcome — burn it like the Herculaneum scrolls and maybe it can still be parsed (though this takes us back in some ways to the skills required for the virtual domain; the point remains that the work is durable).

Physical content is what it is. This means a document represents a relevant point of truth even when that truth is deemed false. The author felt a certain way on a certain topic at a certain time. Even fraudulent documents reputing to be what they are not can be deduced and in doing so now represent a new point-in-time truth of their own.

The level of skill necessary to deduce frauds in virtual content is far removed from the parsing of a physical document. An edited video typically requires deep analysis to differentiate from the real. A Wikipedia page does not show its history on its surface; you can view the discussion page, check its edits, but even this relies on the integrity of the wiki system. If the paradigm of the system fails or becomes corrupted, the metadata becomes meaningless or worse. Framing content like document history and discussion adds effective marginalia to the document and can be compared to physical documents, as well as providing a more useful, more flexible system, but stable such a system is not. We debate virtual media all the time. Its volatility is near total. Physical media perseveres, can be referenced, can be discussed on its own merits.

This is getting long and a bit abstract, I know. Bear with me, we’re nearly through.

I feel I am failing to strike with precision the point I am trying to make, which is effectively only this:

A book, a paper, or anything else held in the hand makes a statement for itself.

What comes after may be built on top it, and vary in outcome, but the physicality represents a base to this structure, something firmer than virtual content ever can be.

The case I make, and others as well, is this: What good can physical media possess in the future? Can there be any continued relevance when the ubiquity, transmission, and ease of creation and access to virtual content is so total?

A cacophony of paper shrieks “yes!” to all who are willing to hear. The utility of physical media remains; the need for it will only increase. Awareness, curation, and transmission of physical media is a commodity against which a stable currency is pegged; for us this currency is verifiable knowledge. In the increasingly abstracted, tortuous, immense virtual world of discussion, debate, information, misinformation, question, answer, confusion, determination, and growth, a stable basis for the beginning of knowledge ranks among the most valuable commodities — at least that is what I think.

* “Virtual” as opposed to “digital” for various reasons…for another post.